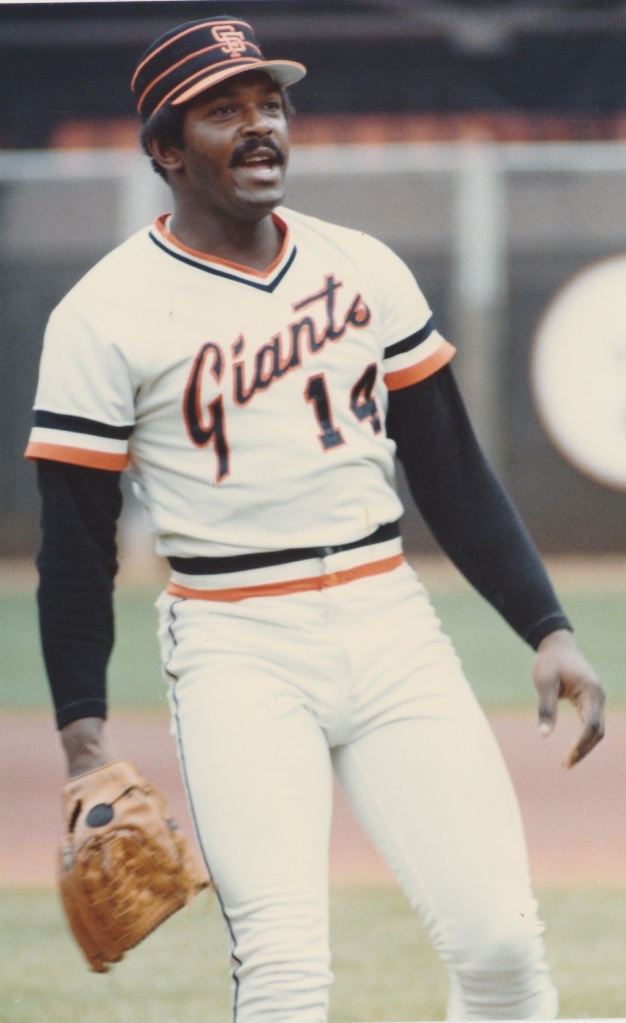

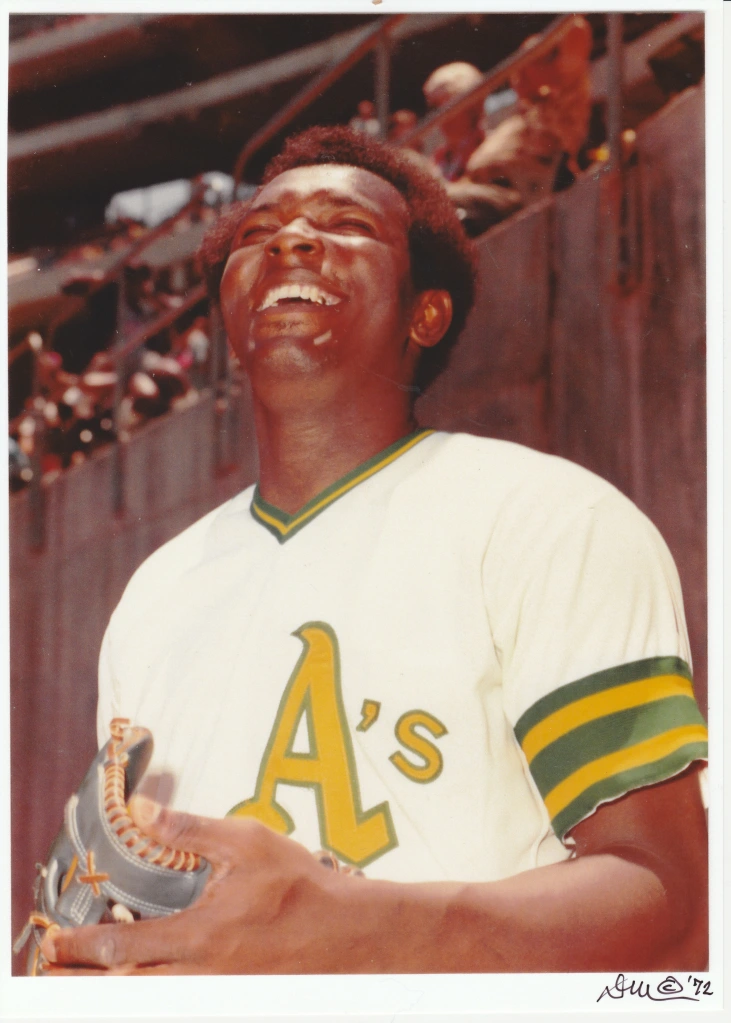

I was devastated to hear the news yesterday about Vida Blue’s passing. He’d been ill for some time, having shown up to the A’s recent reunion of the 1974 championship team needing a wheelchair and cane to aid his diminished mobility, with people close to him now saying that he was holding on as tightly as he could specifically to make that event.

Vida was a towering figure during my preteen Giants fandom in the late-1970s and early ’80s, shepherding their ascent from laughingstock to respectability. I was too young at the time to understand just how impactful the man had been on baseball’s landscape prior to his arrival in San Francisco.

Now, having written Dynastic, Bombastic, Fantastic, about the Swingin’ A’s of the 1970s, I now know better. Vida played an outsized role on those three-time champions, having taken the baseball world by storm in 1971, butting heads with Charlie Finley during a ruined 1972, and rebounding to place three top-10 Cy Young finishes over the next four years amid whirling rumors of being traded or sold outright, and watching the rest of the roster depart at the dawn of the free agency era while he was left to languish in Oakland.

I’ve spoken to Vida at ballparks, at symposiums and in classrooms. He even took to calling me on occasion to fact-check some conversation he was in the middle of having (usually, it seemed, with a date he likely wanted to impress). The four hours I spent with the man over lunch at the Claremont Hotel in Berkeley back in 2015, however, while researching Dynastic, was the most concentrated and wonderful dose of Vida one could hope for. That’s where he gave me the line that I chose to head the book’s epilogue: “We were the team everybody wanted to come see: the freaks with the mustaches, with the long hair, that took batting practice in black shoes but came out to play in white shoes.”

He also noted the A’s primary colors during his run with the team: Wedding Gown White, Fort Knox Gold, Kelly Green and Vida Blue.

Although Vida ended up having a nice career, he proved unable to sustain his early dominance. There are many reasons for this, including overuse during that 1971 campaign and his subsequent holdout in 1972. None are more prevalent than a spiraling drug problem that saw Blue not only suspended for the 1984 season following a cocaine conviction, but serving three months of jail time at the beginning of that year. He rejoined the Giants in 1985 and hung on for a couple more seasons.

Blue’s career was one of what-ifs. Nobody was more aware of this detail than Vida himself. “I blew it …” he told The Washington Post in 2021. “I can honestly, openly say I wish I was a Hall of Famer. And I know for a fact this drug thing impeded my road to the Hall of Fame … so far.”

That’s not how I like to remember him. I prefer to consider the young, cheerful wunderkind who took the American League by storm in 1971. To that end, I offer an extended excerpt from Dynastic:

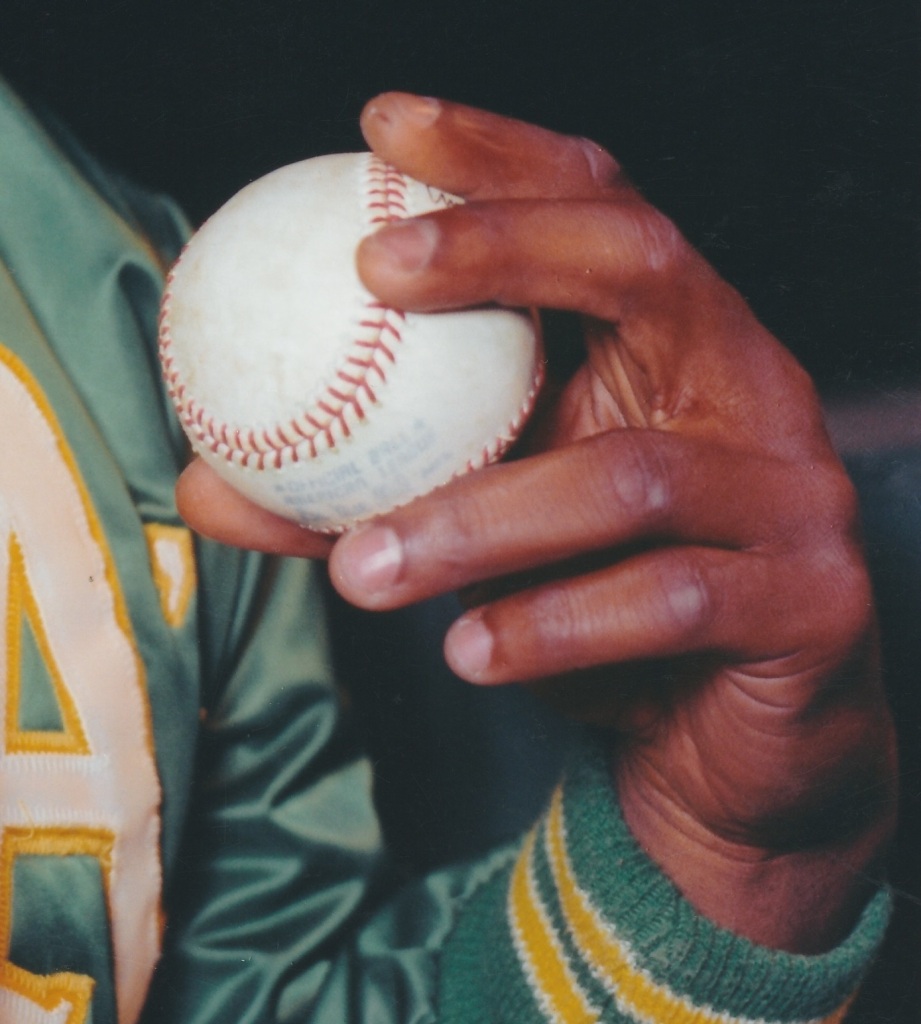

The real story of 1971 was Vida Blue. Six feet tall and 190 well-packed pounds, the left-hander threw devastatingly hard and with disarming ease. His windup featured a uniquely high leg kick that brought his right knee almost to his chin, and a delivery in which he reached so far back with the baseball that his knuckles nearly scraped the dirt. He’d made his debut as a 20-year-old call-up the previous September, and pitched a one-hitter against Kansas City in his second-ever big league start. Blue couldn’t throw anything but fastballs, but that was enough—the ones that didn’t drop like bowling balls exploded so ferociously upon reaching the plate that hitters swore they saw them rise. Two starts after baffling the Royals he no-hit the Twins. “We never even saw the ball,” marveled Minnesota’s Harmon Killebrew afterward, “but we sure heard it good.”

Blue’s marvelous September earned him the nod to pitch the Presidential Opener in 1971, but the magic didn’t last. The young lefty surrendered four runs in one and two-thirds innings, and Oakland lost, 8–0. Things, however, would quickly improve.

In Blue’s second start of the season he set a franchise record with 13 strikeouts over six shutout innings of a rain-shortened game. His third start was a two-hitter over Milwaukee. His fourth start was an 11-strikeout victory over the White Sox. Vida, who had spent his winter working on a curveball, was somehow even better than he’d been the previous September. Following his disastrous opening assignment the lefty won 10 straight, compiling a 1.03 ERA while spinning nine complete games in 12 starts.

“There are some guys you go hitless against and it doesn’t bother you,” noted Baltimore outfielder Paul Blair. “What you tell yourself is, Well, I got a piece of him, or at least I fouled one off. But this guy makes you go 0-for-4 and you feel humiliated. He doesn’t give you a single thing. He strips you naked right there in public. Trying to hit that thing he throws is like trying to hit dead weight.”

By early May the country was paying attention. Sports Illustrated compared Vida to Sandy Koufax. (“That’s funny,” responded Blue, “I don’t look Jewish.”) Soon he would grace the covers of Time and Newsweek, publications that didn’t ordinarily cover sports, and hold down guest spots on NBC’s Today Show and The Dick Cavett Show. Talk began in earnest about his chances of winning 30.

On May 28, more than 35,000 people crammed into Fenway Park (capacity: less than 34,000; average: 16,000) to watch Vida pitch. On June 1, he attracted more than 30,000 to Yankee Stadium for a game that would have otherwise drawn about 12,000, and the A’s suffered through a pregame clubhouse so crowded with media that Dick Williams called a team meeting just to clear the room. Back home 47 percent of all Bay Area TVs tuned in as Blue won his 12th, another complete game. By that point Charlie Finley was seeing dollar signs in everything his young star touched. Vida, scheduled to pitch only once during an eight-day homestand, was given Catfish Hunter’s slot on June 17, which served the dual purpose of providing Blue with an extra home date and knocking him from his previously scheduled spot ten days hence, which corresponded with Bat Day at the Coliseum. “We didn’t want him to pitch on a promotion day,” Williams explained. “He’s enough of a promotion himself.”

Vida’s sheer exuberance could not be suppressed. During games in which he didn’t pitch he sat in the dugout and listened to Williams rant about on-field mistakes, then would approach the skipper, a smile on his face, to say things like, “I’m going to tell Greenie [second baseman Dick Green] what you all said about him. I’m going to tell him as soon as he gets off the field.” Reggie Jackson called the pitcher a “dugout instigator, like the rest of us, but always in an innocent way.” Vida wore a Joe Namath–model New York Jets jersey while tossing footballs with clubhouse kids before games, then proceeded to run them ragged. “George, you my man, get me a soda pop,” he’d call out. “Steve, how ’bout wringing out my shirt here? Chuck, get me a dry sweatshirt.” Chuck, of course, also went by Mr. Dobson and was at the time of the request the starting pitcher for that night’s game. The right-hander politely declined. “Oh,” said Vida. “I knew I’d go too far.”

…

By the middle of July 1971, Blue’s 17-3 record and majors-leading totals in wins, shutouts, strikeouts, and ERA earned him the starting nod in the All-Star Game. Every one of his victories had been a complete game. Even his no-decisions were spectacular: on July 9, Blue struck out 17 Angels over 11 shutout innings, but the A’s didn’t win until the 20th. Said Jackson, “You can even get the Babe out of his grave and he’d look at Vida and say, ‘The man’s too much.’”

Blue’s 18th win was a one-hit shutout of the Tigers in his first start after the All-Star break. It was also his 18th complete game of the season, and the innings were taking a toll. The lefty exceeded his career-high of 171⅔ innings by the second week of July, and two weeks later he passed 200. In Blue’s first attempt at his 20th victory, on July 30, he gave up four earned runs in six innings—only the third time all season he’d allowed that many—and lost. “I’ve never been more tired,” he complained afterward.

The pitcher, at first delighted by the accolades, grew overwhelmed by them. His attention was drawn taut by the national media, then segmented to slake the public’s thirst, one feature story at a time. “I wake up and then I’m at the ballpark,” Blue said, head spinning. “I’m pitching. Then it’s all over. I’m back in the dressing room and writers are all around me. Then I’m on an airplane. I’m in a hotel. I’m at the ballpark. Now I’m back in Oakland. Now Mr. Finley is giving me a car, and my mother and my brother and my sisters are there. Now lights are flashing. Now I’m pitching again.” No one ever said being a phenom was easy.

Blue’s roommate, Tommy Davis, took to screening calls for him at home. Vida signed so many autographs that he began using his right hand in order to save his left one for pitching. Over the course of the summer he went from “I want to sign ’em all . . .” to “You got to sign, you just got to . . .” to “You don’t got to sign. You don’t got to do nothing but die.” Still, he signed. By August, Vida was lamenting that “I sometimes feel like I’m going to crack up mentally.”

The interview Blue gave to reporters following his 20th victory, on August 7, was so dour as to be described as “hostile” by one reporter. Somebody asked whether the win would help Vida remove the monkey from his back, and the pitcher gripped his head. “There was no monkey on my back,” he yelped. “There just was the pressure, that pressure.” Somebody brought up the specter of 30 wins, and Vida snapped. “There you go again,” he yelled, slapping a table. “There’s that’s damn pressure.”

Vida won his 22nd with 10 starts left in the season, and though he’d have to succeed at an absurd pace to reach 30, people still held out hope. By the end, however, he was just a gassed pitcher trying to get by. Blue was blasted out of starts earlier than ever and won only twice more, ultimately finishing second to Detroit’s Mickey Lolich in victories.

Still, the kid had been spectacular. Vida’s final line: 39 starts, 24-8 record, 1.82 ERA, 24 complete games, eight shutouts, 301 strikeouts, and 88 walks in 312 innings pitched.

***

In the process, Vida became the youngest player ever to win the Cy Young or MVP Award, let alone both in the same season. He was the jolt of fresh, young energy that baseball needed, but burned too bright, too fast, and could not sustain it.

None of that diminishes the man’s place in baseball history, nor will it make him any less missed. The sport is already poorer without him. RIP, Vida.